No products in the cart.

Return To Shop

Log in / Sign in

Login

Register

Will Peace Return? Trauma and Health-related Work in Kashmir

₹ 50

Sahba Husain, in her capacity as a consultant with Oxfam, worked in Kashmir at a time when the conflict was already 15 years old. This essay discusses her experiences as a part of the Violence Mitigation and Amelioration Project, where her task was to examine the psychological impact of violence on people's lives as well as the echoes of such violence. It brings to the forefront the increasing rates of psychological disorders and cases of suicide, and the utter paucity of resources for dealing with the deteriorating mental health situation in the region. The essay’s observations on trauma and health stem from the author's empirical study of the population of Kashmir, for whom life has been rendered uncertain. Husain explores how faced with loss, suffering and prolonged stress, women in the region have become susceptible to depression and anxiety too, but often cannot seek treatment due to social constraints. By capturing certain experiences of the people, the essay evokes the drastic transition that has taken place in their lives after militancy and has left Kashmir in the dark. The refrain of fear that is pervasive in the region only affirms that no one, irrespective of age, gender or class, has escaped the massive impact that militancy and the AFSPA have had. Husain's piece is a reflective one as she discusses the challenges she faced during her work, which were integral to her subsequent disillusionment with the Indian state . Her essay, too, shatters a certain monolithic image of Kashmir and sheds light on the psychological trauma and health issues that people from the Valley face. It is, finally, a reminder of the patience, endurance and strength that women have displayed in their desire for justice, and above all, peace.

Add to cart

Dealing with Conflict and Violence: The Power of Attitude

₹ 50

This piece was written after the abduction of the author's husband by ULFA terrorists in Majuli, Assam where they worked as social development workers in 1996–97. In this chapter, Ghose explores her experience of learning to cope with the aftermath. Moving from personal reflections to discussing universal aspects of such suffering, she throws light on the far-ranging impact of violence that often goes unacknowledged. She then captures the different stages that an individual undergoes in the period of suffering, and consequently looks at strategies of coping which are effective and can transcend harmful responses. By shifting the focus onto the individual's own reaction to violent events, Ghose is able to break down the mistakes that one is susceptible to making almost reflexively – mistakes that perpetuate a cycle of violence.Written in the form of a prefaced monograph, the title of this piece is drawn from a short course that the author attended in Delhi, which gave her the fresh perspective and strength needed to make this reflective essay a reality. Ghose's insights on responding to events of violence or conflict are embedded in a critique of certain forms of protest as well as what she calls the commonly held 'victim attitude'.For Ghose, strategies of coping become methods of achieving much more. In a world full of violence and rage where a vicious cycle of the two is kept alive, it becomes imperative to rise above feelings of aggression and victimisation that inevitably cause more harm than good.

Add to cart

Health and Torture

₹ 50

The essay traces the detrimental effects on the health of the people of Nagaland due to excessive militarisation in the region. Ngully puts the idea of 'health' into perspective and examines the implications of the WHO definition, which cites not just physical, but also mental and social well-being as criteria. This is done with regard to the torture, murder, and rape that the Naga people have been subject to in the past years by the security forces, justified under the cover of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA).By placing the psychological trauma that the Naga people have faced within a broader context of disorders resulting from large-scale manufactured disasters, Ngully lays emphasis on the scale of tragedy in his homeland. There is a certain universality to the potential effects that such disasters can have on the mental health of survivors, and these can last long into the aftermath. The effect on mental health, then, Ngully argues, is an important component of disaster impact.The essay also looks at torture as a term used to describe the atrocities being committed by the security forces and briefly draws a picture of its actions, which have effectively led to a war-like situation. Ngully finally concludes with a call to civil society for the various kinds of help that they can extend in order to mitigate the effects of such a crisis.

Add to cart

The Campaign Against Dowry

₹ 50

Radha Kumar's chapter tracks the history of protests against dowry in the contemporary women's movement, starting from the first demonstrations at Hyderabad in 1975 and leading up to significant legal amendments in the early 1980s. Interspersed with historic photographs of the movement in its crucial stages, the essay captures the wave of protests that spread across the country, bringing disparate groups together to revolt against dowry-related crimes.As stories of torture were brought to attention in public discourse, feminists challenged the dominant ideological mode that rendered violence against women a private, family matter. This violence was not only physical, but also mental, often leading to incidents of bride-burning and abetted suicide. Kumar's essay delves into the way such incidents garnered public outrage – particularly in Delhi, where the campaign was more sustained – and how, over time, feminists expanded their methods of seeking redress. The campaign, as it gained traction, sought action not only through legal investigation, which had been negligible in dowry crimes, but also through social pressure on the perpetrators.Kumar's essay finally covers the consequences of the prolonged campaign, in particular those of changing legal attitudes. There had been a marked shift from an indifference regarding practices of dowry harassment and bride-burning to a series of amendments that set in place several protective as well as investigative measures for cases concerning dowry victims. The movement had then achieved, after initial setbacks, some important victories, and Kumar's essay captures this not only through its text but also through a range of photographs from the period.

Add to cart

Finding Face: Images of Women from the Kashmir Valley

₹ 50

Sheba Chhachhi's piece offers an alternative to the visual landscape of Kashmir which, in the popular imagination of people today, is occupied by the ravages of war and countless martyred men. By placing itself as an invitation into a private space that is rarely, if ever, breached by dominant media discourses, this photo-essay highlights the absences in the pictures of carnage that are used to fuel propaganda on both sides of the conflict.The piece – comprising of a critical essay and a series of personal testimonies which are interspersed with photographs – seeks to bring human figures back into the landscape and give voice to those whose lives have been obscured in the din of a prolonged war. It makes space for the individual in a history of representation that is populated with recurring tropes and warring stereotypes which, Chhachhi argues, depersonalise the Valley and its conflicts. In her work, women are no longer silent victims, they emerge as textured human beings, not only with voices with which to speak, but also with eyes that are wide open. The testimonies have been taken over a period of six years and reflect varying positions, and the interviewees are students and professionals, Muslims and Pandits, teenagers and the aged.The photographs are extracted from a larger work which was initially presented as a photo-installation by Sheba Chhachhi and Sonia Jabbar. The photo-essay as a whole captures the life and times of women during conflict, including during the attempted implementation of the burqa diktat in the Valley. These individuated women stand out in the frames as they look back at the viewer in more ways than one.Please note that the photographs contained in this essay have been directly scanned from the printed book due to the non-availability of the originals.

Add to cart

Kidnapping, Abduction, and Forced Incarceration

₹ 50

In 'Kidnapping, Abduction, and Forced Incarceration', the authors examine, first, the various methods of kidnapping/abduction and forced incarceration—on the basis of a study of 47 narratives—and then analyze these forms of violence’s implications for Dalit women’s fundamental rights.An examination of the relationship between kidnapping/abduction and forced incarceration, and violence concludes that non-state actors employ the method of forced incarceration to mete out punishment in the form of sexual and physical assault against Dalit women who do not conform to caste-class-gender hierarchies. An analysis of the study data, write the authors, shows that there are three broad categories of methods of kidnapping/abduction: the use of force, allurement through false promises, and other false allurements or ruses. Often, more than one method is utilized; throughout these categories, verbally coercive tactics (like threats) were used to further intimidate or torment the target.

The essay also notes that state actors, primarily the police, engage in their own forms of forced incarceration by the filing of false cases or the illegal detention of Dalit women. Unlike with non-state agents, the authority of a single police official, as a member of a dominant caste and as an agent of the state, is enough to successfully enforce an incarceration. This, the authors assert, shows the ascendency of caste norms over the rules of law.The physical isolation and restriction from dominant caste male-dominated public spaces re-emphasizes and compounds the caste-class-gender-based social exclusion and vulnerability to violence that Dalit women face, argue the authors. Kidnapping/abduction and forced incarceration are used to both degrade Dalit women’s identity and to mould a collective negative identity fashioned along inequitable caste-class-gender parameters, conclude the authors. Kidnapping, Abduction, and Forced Incarceration thus highlights how these forms of violence negate their agency and reinforce notions of passive submission to exploitation and violence at the hands of the dominant caste.

Add to cart

Surviving Violence, Making Peace: Women in Communal Conflict in Mumbai

₹ 50

Kalpana Sharma's essay explores the multiple roles that women came to occupy in the riots that took place in Mumbai post the Babri Masjid demolition. As the news of this destruction – carried out on 6th December 1992 – was broadcast across the country, it triggered communal violence, resulting in two phases of riots between the Muslim and the Hindu communities. The essay looks at the people who were some of the most affected by the carnage in the city, the urban poor, and highlights how their specific spatial and economic locations had a great bearing on their lives in this period. By studying the chawl dwellers, the slum inhabitants, and the people who resided on the pavements and analysing how each group had varying responses to the riots, Sharma's study explores what degree of significance their religious identity held during this time.Sharma argues in her essay that the role of the women during these riots was not defined by their gender identity alone, or even their religious affiliation, but also by their class and their location in the metropolis. Her essay is an attempt to understand why and how these factors held the importance that they did, as her study spans areas of Mumbai which were all affected directly by the chaos. She adopts and reinforces a perspective that is broad, in that it explores women's roles during the riots not only as victims, but also as active participants, ready to fight for survival, and as peacemakers who played key roles in bringing communities together in difficult times.

Add to cart

Personal Law and Communal Identities

₹ 50

Feminist movements in India have, both pre- and post-Independence, seen the family and home as the nexus of organizing women’s lives. By the early 1980s, attempts to analyse this nexus had led to examining the codification of women’s rights in marriage and property. It is in this vein that this essay considers the history of the 1985 Shah Bano case and the feminist debates on personal law that it gave rise to.

The call for a common civil code that emerged from the case was extensively critiqued by feminists, liberals and secularists, as well as Muslim religious leaders. The essay traces how the sociopolitical context led to the quick descent of the issue into communal agitation, with a demand that Muslims be exempt from Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code that had been cited in granting Shah Bano maintenance from her husband. It describes how Hindu communalism had been acquiring legitimacy in the eyes of the state, and the contribution of this factor to the national fervour surrounding Shah Bano’s case.

Kumar then traces the opposition by various women’s groups to the 1986 Bill, which was introduced in parliament with an aim to exclude divorced Muslim women from the purview of the hotly debated Section 125. She explores the ‘bitter lessons’ that Indian feminists learnt from the public and state responses to Shah Bano’s case, which then posed certain questions that would become increasingly important to feminists in the years to follow. She concludes with questions of secularism–its definition and its practice–and of representation, both of which are brought to the forefront by Shah Bano’s case.

Add to cart

Crab Theology: Women, Christianity and Conflict in the ‘Northeast’

₹ 50

This essay addresses the role that religion plays in sociopolitical processes in Mizoram by attempting to gauge the impact that churches have had in mediating conflicts and brokering peace in the state since the 1960s. It also examines the role of women (and lack thereof) in peacebuilding processes and explores gendered critiques of the same.

As Sawmveli and Tellis write, churches in Mizoram are centralized bodies that hold immense power, thus enabling church leaders to aid Mizo ‘militants’ in negotiating with the Indian government as early as 1966, when insurgency first broke out. However, women did not have much of a decision-making role, neither within the clergy nor during negotiations. The lack of women’s participation can be explained, according to the authors, by the entrenched patriarchy and misogyny in Mizo society. In fact, interviews with Mizo women reveal that they acknowledge the crucial role the church played in mediation, but did not see their exclusion from the process as an issue.

The essay further states that since most political parties in the region are aligned with churches, patriarchy in politics overlaps with patriarchal church culture to marginalize women. However, they also discuss the many women’s organizations that have come up over the years to facilitate women’s entry into the public sphere. Women are also reclaiming traditional proverbs that were used to oppress and belittle them—the essay cites Lalrinawmi Ralte’s rewriting of a popular saying that devalues women as crab meat in the form of what she calls ‘Crab Theology’.

Add to cart

Khasi Matrilineal Society: The Paradox Within

₹ 50

Esther Syiem's essay traces the paradoxical nature of women’s status in Khasi matrilineal society. At once empowered and oppressed, Khasi women learn to negotiate these contradictions in their day-to-day engagements with society. Matriliny, for example, is often seen as empowering for women: this, combined with more egalitarian tribal traditions and culture, has given Khasi women greater visibility and mobility and has helped to build solidarities among them.

Despite being both visible and vocal, like their sisters across the country Khasi women too face a skewed sex ratio, a lack of reproductive choices, widespread domestic violence and a host of other issues. The author suggests that these contradictions are better understood by looking at the origin of the Khasis, a time when, because men went to war and often did not return for long periods, women were designated as keepers of the family name and of social values. These became their domain. While inheritance passed through them, much decision-making power in public spaces, particularly in the field of politics, stayed in the hands of men. Although culturally and legally, for example, there is no bar to Khasi women participating in politics or standing for elections, but by and large, despite being ‘empowered’ in other spheres, women tend to stay out.

With the breaking down of the relative isolation of tribal cultures in India, and with more women stepping out of their homes and seeking jobs, change has begun to seep into Khasi lives and transform old relationships and equations. Pointing to this as an important development, the author pleads for Khasi society, and Khasi men in particular, to be open to this change, and to embrace it without limiting the agency of women.

Add to cart

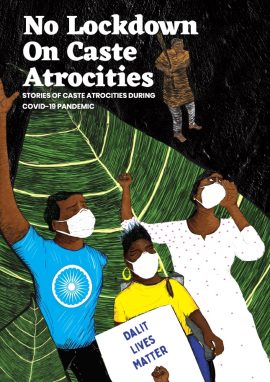

No Lockdown on Caste Atrocities: Stories of Caste Crimes During the COVID-19 Pandemic

₹ 0

As India went into a nationwide lockdown to fight the Coronavirus pandemic, caste animosity continued its rampage and destroyed the lives of thousands of Dalit persons across the country. The book No Lockdown on Caste Atrocities: Stories of Caste Crimes during the COVID-19 Pandemic produced by Dalit Human Rights Defenders network (DHRDNet) tells stories of 60 such cases of caste crimes that took place while the country was under lockdown in order to deconstruct the psycho-social and legal dynamics that perpetuate caste violence.

DALIT HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS NETWORK (DHRDNet) is a coalition of over 1000 Dalit human rights defenders from across India. The main objective of DHRDNet is to create an efficient network of leading Dalit Human Rights Defenders to combat the rights abuses and to ensure that antidiscrimination mechanisms are properly and thoroughly implemented.SALMA VEERARAGHAV is a certified Communications professional from Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. She is the Founder of C4C, and has over two decades of work experience with International NGOs, domestic NGOs, Television Industry and the Education sector.

Add to cart

DALIT HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS NETWORK (DHRDNet) is a coalition of over 1000 Dalit human rights defenders from across India. The main objective of DHRDNet is to create an efficient network of leading Dalit Human Rights Defenders to combat the rights abuses and to ensure that antidiscrimination mechanisms are properly and thoroughly implemented.SALMA VEERARAGHAV is a certified Communications professional from Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. She is the Founder of C4C, and has over two decades of work experience with International NGOs, domestic NGOs, Television Industry and the Education sector.

Contact Us

© Zubaan 2019. Site Design by Avinash Kuduvalli.

Payments on this site are handled by CCAvenue.