No products in the cart.

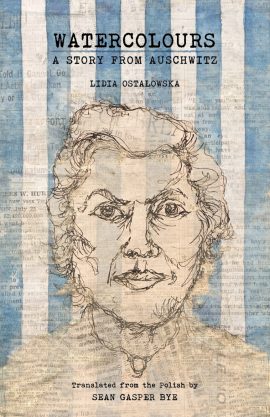

Return To ShopThe following are two excerpts from Watercolours: A Story from Auschwitz by Lidia Ostałowska, translated by Sean Gasper Bye. ‘Céline Sings’ is from pages 42-44. ‘Watching a Performance’ is from pages 51-55.

Translator’s Note

It was Dina Gottliebová-Babbitt’s artistic skills that allowed her to survive Auschwitz. After her imprisonment in Auschwitz-Birkenau, she had painted a mural of Snow White in the children’s barrack of the so-called Familienlager, a section of the camp which held prisoners from the Theresienstadt ‘model’ ghetto. An SS officer saw the mural and recommended her to the camp doctor, Josef Mengele. Mengele was conducting horrific pseudo-scientific experiments on prisoners to ‘prove’ the Nazis’ theories of racial inferiority. Unsatisfied with the quality of colour film in the camp, Mengele engaged a team of artists to make medical illustrations for him. Dina’s job was to paint portraits of his Romani test subjects. So long as she did a good job, Mengele would keep her alive.

Both Dina and her portraits survived. Dina made her way to America, while the portraits, thought lost, re-emerged decades after the war. Enshrined in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum’s permanent exhibition on the Romani genocide, they became the subject of a long-running ownership dispute between Dina and the Museum. Were they works of art that belonged to their painter? Or were they documents, a major part of the very limited evidence of German war crimes against the Roma, which ought to stay in the museum? Over the decades, artists, Romani advocacy groups, and the Polish and American governments all took sides in this dispute. Dina died in 2009 – the paintings remain at Auschwitz.

Lidia Ostałowska’s telling of this powerful story interweaves Dina’s life with the history of the camp both during and after the war, tracking how cultural memory of the Holocaust has evolved over the last half-century in Europe, America and Israel. She also poses challenging questions about art and morality. If art is used in service of genocide, is it still art? What are the artist’s duties under such circumstances? And to whom does the artist’s work belong—to the artist? The victims? To humanity?

None of these questions have easy answers and Ostałowska explores them from every angle, drawing on extensive interviews and archival research, including many first-hand accounts from prisoners and other artists who survived the camp. This is a book of emotional depth, exploring the inner lives of Dina and her fellow inmates. But it is also a book of scope and breadth, exploring our changing relationship to this dark place. How did the camp come about? How was it preserved and then consecrated as a museum? How has it evolved as a cultural and political symbol in countries around the world? And what of the small Polish town of Oświęcim that borders the camp, and where everyday life must continue in the shadow of humanity’s greatest crime?

Ostałowska’s approach is sensitive and powerful. In simple prose, she lets this story speak for itself without sentiment or embellishment. She does not shy away from the complexity of these issues and does not allow us to rush to simple conclusions. Watercolours is a unique, probing history of the Holocaust and its long shadow: the effects it has had on survivors, their families, countries, cultures—and of course, on Dina Gottliebová-Babbitt herself. It is a powerful piece of literary journalism and a book sure to linger in the memory long after it has been read.

— Sean Gasper Bye

Céline sings

Lidia Ostałowska

There was a small room in the sauna next to Mengele’s surgery. Dina: ‘I’d call it a studio. Mengele gave me watercolours, a brush and a drawing pad. I’d never painted with watercolours before, though – we’d only had oils and tempera paints in school. there was no easel – I got two chairs instead. I sat on one and propped the drawing board up on the other. and I got started.’

She began with finding a model, because the doctor hadn’t chosen one, he’d only said, ‘go and pick someone.’ Dina walked out of the barrack.

‘I chose the first person I saw – a girl wearing an elaborately tied, very colourful headscarf.’

The painting took two or three days. It was a left-facing three-quarter view, with a caption underneath: Zigeuner- Mischling aus Deutschland, ‘Gypsy Half-Breed from Germany’.

‘I instinctively signed it in pencil: “Dinah”. Mengele noticed, but didn’t order me to erase it. the portrait didn’t come out very well, but he was happy. Nowadays I think the first portrait was the worst. I hadn’t done separate sketches.’

The technique of watercolour painting is only simple on the surface. Dina knew how much skill and practice were required. the pigment (bonded together with gum arabic) is mixed with water, and this water is what alters the intensity of the color. There’s no white paint on the palette, the artist uses the white of the paper to give the effect of light. You can’t spoil the paper with pencil marks – a few coloured dots, and that’s your sketch. There’s no question of making corrections. Each stroke of the brush must be perfect, because it is final.

She must have been frightened, although she never admitted as much in her testimonies. All the while she was clinging to life. Had she been saved by the all-powerful Mengele, the scrawny Dr König or snow White? It didn’t matter, now she was totally dependent on her artistic talents.

After the success of the ‘Gypsy Half-Breed’, she went out among the stables with a new commission.

It was chaos, a jumble of Gypsies in ragged clothing. How can you do laundry with no water, how can you mend clothes without needles or thread? The ss officers would march men up and down the gravel lagerstrasse ‘for punishment’, bellowing orders. turn in a circle, do a squat, roll about on the ground, sing. Most often they would sing Das kann doch einen Seeman nicht erschüttern, ‘that can’t shake a seaman’. Hollow-cheeked children wrapped their arms round their instruments, and the violins and guitars seemed larger than the children themselves.

In this wretched throng, a young Gypsy girl with a blue scarf tied round her neck stood out.

‘I removed that scarf and draped it over her head. I asked her to smile a little. She told me her two-month-old daughter had just died because she couldn’t breastfeed. After that I stopped asking people to smile.’

(All the children born in the Zigeunerlager died. there were 378 of them.)

This girl, Céline, was suffering from diarrhoea.

‘She couldn’t digest swedes or black bread. So I asked for some white bread for her and, on Mengele’s orders, I actually got it. There was this tall, handsome man there, a czech in a white uniform. He worked as a waiter for Dr Mengele. Every day he brought me a little bread. It helped her.’

Dina whispered to Céline.

‘I tried to sing a French song, but I couldn’t remember it. she helped me along. She knew the words, so she must have been French. She looked like a porcelain doll or a prima donna. Gazing into her eyes was like gazing into her soul. You can see that in the painting.’

Now and again the doctor would check on her. Although he usually avoided physical contact with the prisoners, he himself pushed the blue scarf behind the Gypsy woman’s ear to reveal it: the ear was considered important in the study of race.

But it damaged the composition.

‘That ear makes the picture look odd.’

Mengele accepted the portrait of céline, but declared he would select the next subjects.

‘The ones he picked were older and less attractive. they were men. I chose women.’

Now Dina took her time at her primitive easel.

‘When I was working in the Gypsy camp, I didn’t have to report for roll call, I didn’t have to do anything, just paint. When Mengele went for his mid-afternoon meal he’d bring something back for me to eat as well. It was the only time I felt human in auschwitz. I took my time.’

This was her new routine. Two weeks – one watercolour.

Watching a performance

Lidia Ostałowska

She observed everyday life in the barrack. ‘They maintained a peculiar kind of courtesy, which made it feel like you were in an animal testing facility. It never seemed as though Mengele thought of the Gypsies as people. Sometimes he’d offer them a friendly smile, sometimes tell a joke, usually to Zosia or me.’

He kept bringing people in for portraits. A grey-haired woman, a grown man, a boy… they don’t usually look the viewer in the eye in the paintings, so it’s impossible to return their gaze. there is no communication between us, we are not permitted into the mind of the sitter. And this is significant – in the renaissance, when portraiture was flourishing, its creators took the humanist stance that the face expressed the movements of the soul. The Gypsies’ faces are dead.

They sat on stools before Dina. She never mentioned stools for models in her testimonies, but today art critics can determine it from the pictures. The Gypsies are portrayed like suspects on an arrest warrant. Gunslingers in the Wild West looked the same on nineteenth century ‘Wanted’ posters, and so did al capone when he was arrested in 1931. This technique is called a ‘mug shot’. The well-known american private investigator allan Pinkerton invented it for his famous detective agency. Mug shots aid in police investigations and are employed to this day, including in europe. (That being said, nowadays human rights activists oppose their use. They make everyone, no matter how innocent, look like a criminal.)

Joseph Mengele was taking advantage of Dina’s artistic skill to attain photographic perfection.

This was a tried and tested approach, since watercolours were for more than misty, impressionistic landscapes. Before anyone had reproduced an image using a light-sensitive emulsion, naturalists, geographers and anthropologists on expeditions would pack a light wooden case in their trunk, containing watercolour paints, a sketchpad, badger-hair brushes, pencils, knives to cut the paper and sharpen the pencils, and a water dish. Oil paints dried too slowly to be of any documentary use. Watercolours were cheaper and simpler.

on the eve of the First World War, the anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski brought a new invention on his voyage to New Guinea: a hand-held camera. But he also invited an artist, the famous painter and author stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz. None of Witkiewicz’s paintings from that trip have survived, but we know of others, published in textbooks of zoology, botany and medicine, in atlases and monographs. Books the future Lagerarzt would have leafed through.

Mengele aspired to a professorship so he paid special attention to the illustrations for his thesis. He’d made Dina his private artist (and that’s how she was presented after the war), but he wouldn’t have entrusted his career to a single prisoner. He made the most of auschwitz’s mechanisms. Marianne Hermann, Ludwig Feld, Vladimír Zlamar and Janina Prażmowska all painted the Gypsies or parts of their bodies. Mengele personally photographed the stages of his experiments, as well as instructing others to do so.

One of those photographers was the young Pole Wilhelm Brasse (subject of the well-known film The Portraitist by Ireneusz Dobrowolski). Brasse had trained in a stylish studio in Katowice. In the Erkennungsdienst – the camp Gestapo’s photo studio in auschwitz I – he photographed naked Jewish children. He found it upsetting. He cobbled together a makeshift partition so they had somewhere to undress. This was a final gesture of humanity: when it was over, they were murdered with phenol. In one of the surviving photographs, Gypsy girls sent in by Mengele stand naked in a row: four small children’s faces, terrified, their hair cropped down to the skin.

There are also other interpretations: that these weren’t girls, but castrated Gypsy boys.

Dina painted the Gypsies as Mengele saw them – did she realize that? Or perhaps, as she moved her brush across the page, she decided to soften the portraits?

What does an artist feel under that sort of pressure? Art should not be in the service of genocide. What if it is, and is still a source of pleasure? Even when degraded to photography, to a craft, art makes life possible. How can a person accept that?

Dina had no memory of Mengele’s Gypsy experiments, that’s what she said. But she admitted to hearing of one in the women’s camp.

‘A forty-year-old woman from Berlin, who illustrated fashion magazines and sketched models, was subjected to electrical shocks of different intensities. He wanted to see how much she could withstand. So far as I know, she didn’t survive.’

The people she was painting in the Zigeunerlager were vanishing. Prisoners from the medical team secretly passed on information about the doctor’s experiments, making particular note of some.

Vera Aleksander was a Jew who worked in the twins’ barrack. After the war she recalled: ‘an ss man came and took two children away on Mengele’s orders. They were my two favourites, Guido and Nino, about four years old. Two or three days later he brought them back in a dreadful state. they’d been sewn together like Siamese twins. Their wounds were so filthy they were festering. I could smell the stench of gangrene. The children screamed all night. Somehow their mother managed to get her hands on some morphine and used it to put them out of their misery.’

Vera said the veins in their wrists had been sewn together.

Psychiatrists believe that to survive the camp it was necessary to find a way to distance yourself from it. Those who succeeded in this were present, but not with their whole selves. They were deaf, blind, not taking in the complete experience. They didn’t remember, because they’d banished some part of themselves, condemned it to oblivion. the so-called ‘Muslims’ – those who were completely destroyed, with no will to fight for their lives – truly saw Auschwitz. They perished because no one could survive such a thing. But the mad saw nothing. They retreated into fantasy.

Forty years after the war, the painter Mieczysław Kościelniak admitted on a radio programme: ‘I can’t understand this in myself or in others, but there you have it. Human nature commands you to pass into a fictional life. Fiction was how we survived in the camp. When an audience sits in a theatre and watches a performance, they lose themselves in the story. In the same way, we moved into fiction. although death was raging around us, we believed we’d make it out.’

Dina believes she preserved 10, perhaps 12 Gypsy faces in watercolour.

Where did these Gypsies come from?

What were their names?

Were they frightened?

What happened to them?

There are no details in her mind.

‘I don’t remember anything exceptional about my subjects. They never asked for anything and I wouldn’t have been in a position to answer anyway. Instead, they were stoic. They sat there and didn’t speak to me. The only one to complain was the girl in the headscarf.’