No products in the cart.

Return To ShopGrowing up, we look for personal connections with everything we encounter, such as toys, books or movie characters. While reading, seeing a bit of themselves in the story helps make reading itself appealing to younger people. In India, children grow up reading an assortment of books which are not always context-specific. Due to the abundance of ‘foreign’ literature, much of the popular youth fiction here has white leads living in distant lands with traditions quite alien to the large majority of readers. Not finding any characters like us we, despite colonial histories, end up awkwardly fitting ourselves into the white universe of the stories, glorifying white culture and “whiteness” in general, as the default way to be. How many of us have despaired at not being able to have clotted cream with scones, with only vague ideas as to what either of those actually are?

Representing various kinds of people in literature is important. It doesn’t only serve the purpose of normalising diversity among people. It also helps to broaden the young reader’s imagination of the ‘other’ – of ‘developed’ or white countries, by opening up nuanced discussions about all the people living in these places. It chips away at the hegemony of the white narrative, introducing the varied groups which live in ‘white default’ countries, telling the stories of their oppression and struggle for acceptance. Lack of representation in literature might make life harder for the children of the South Asian diaspora, reducing their visibility, and therefore, often de-legitimising their rights.

The existence of a politico-cultural hierarchy between the ‘East’ and the ‘West’ often translates into quite strong experiences of discrimination and identity confusion for South Asian children born, or largely raised in ‘Western’ countries. They look South Asian, but they speak the language of their own home country and share its traditions, instead of that of their parents’. These children are born with a complex jumble of identities, juggling multiple languages, varied expectations, and sometimes religious prejudice, all the while balancing their personal desires and the everyday struggles of growing up. For these young people, representative fiction can be a place where they find people just like them, to whom they can relate.

South Asian diaspora literature features a diverse array of leads, each fighting their own battles in a bid to find their place in countries which are often suspicious of them, while still holding on to their families and their heritage. They have unique crises, ranging from terrorism to pimples. They also tell children about others like them, across the world, in other countries, helping shed some perspective on their situations, offering the knowledge that others of their age also face troubles, which are sometimes even greater in magnitude.

Young Zubaan believes in this spirit of inclusion, in books which help young people accept their differences as parts of themselves, rather than something which needs to be destroyed.

Here are 6 representative books by writers from the South Asian diaspora, which explore the experiences of South Asian children in general, offering readers a lot to mull over.

1. Radhika Takes the Plunge – Ken Spillman (2014)

For younger readers who have just begun to notice their “difference”, Ken Spillman’s book is a gem. Quirky design and larger print make it easy to read. Radhika has just moved to Australia with her parents, who are overly paranoid and protective, in her opinion. All of her new friends are as comfortable in water as fish, and she longs to join the team—if only her mother would let her!

The story follows her adventure at the pool as she finally learns how to swim. In the process she gets over her fears, including that of standing out from the crowd. She also finds out a secret about her mother’s past, which helps her to understand the restrictions placed on her. The book gently nudges younger children to be patient with their parents whose parenting may be different from that of their friends’, and retain confidence in their own abilities, even when they are under question.

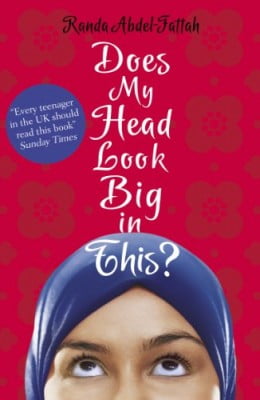

2. Does My Head Look Big in This? – Randa Abdel-Fattah (2005)

Randa Abdel-Fattah’s book explores a situation where a young girl in a white, Christian-dominated country decides to wear the hijab full-time. Amal is an Australian of Palestinian Muslim heritage. Religious and brave, she starts the third term of Year Eleven at her exclusive grammar school with a scarf on her head. Supported by a few faithful friends, as well as her loving parents, Amal navigates the world of casual racism, including facing slurs like ‘nappy head’, alongside the regular pressures of any other school-going teen. Featuring other characters dealing with diverse crises, like Eileen (the daughter of Japanese immigrant parents) and Simone (a teen struggling with an eating disorder), the book delves into multiple themes which might be close to the hearts of conflicted young adults.

What does it mean to be a Muslim? How does one practice one’s faith in a non-supportive environment? How does it feel to constantly be viewed as the expert when it comes to Islam, in school? The book asks tricky questions, tying them up in the end with the feeling that one’s identity and friendships may be guided by culture and religion, but need not be defined by it.

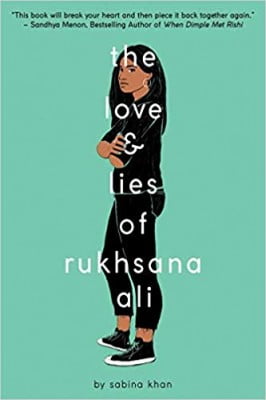

3. The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali – Sabina Khan (2019)

This book by Sabina Khan raises important themes like parenting ethics and the right of a child to make her own choices. Rukhsana, a young high-schooler, is in love with an American girl. More importantly (to her), she has a scholarship to Caltech. Her Bangladeshi parents are well-meaning but conservative, with her mother practicing son-preference and policing Rukhsana. When her parents find out about her sexuality, she is whisked away under false pretences to Bangladesh, abandoning school and scholarship, to find a ‘good Bengali boy’ that she must then marry so that she can walk on the ‘right path’. Rukhsana manages to make allies and return to her country, but not before going through a lot of trials which threaten to separate her from her family forever.

The book depicts the predicament of families of the diaspora, showing the importance of communication and trust in maintaining the fine balance between the traditions of the older generation, and the evolving needs of the younger ones. Relationships within the ‘family-first’ Bangladeshi culture are also beautifully portrayed, such as Rukhsana and her brother’s, Rukhsana and Nani’s, and those within her strong woman-only friend circle.

4. Aru Shah and the End of Time – Roshani Chokshi (2018)

The delightful fantasy by Roshani Chokshi kicks off an epic series around Aru, a reincarnated Pandava from the mythological Mahabharata. It’s presented by Rick Riordan and smells distinctly of his inimitable style of rebooting popular mythoscapes. Aru is a middle-schooler in New Jersey, living with her archeologist mom. Not very popular at her posh school, she often makes up lies to fit in. She lights a cursed lamp under pressure from her classmates who believe they’ve caught her in one of her lies, and inadvertently sets free the Sleeper, a shadow monster out to destroy the world. It’s up to Aru and her divine sister Mini to save humanity, their quest taking them to the celestial council of guardians to be claimed by their god-fathers and through the Underworld, as they fight any number of monsters to activate their weapons for the final battle.

The story takes the characters and settings from the Mahabharata, but the events are all new. A fascinating guide to the world of Hindu mythology, it presents to children a digestible version of the Hindu epics, with just enough modern twists to make it feel cool. For Indian children living away, it’s a dose of heritage wrapped in the garb of a fiercely feminist fantasy, with the potential to instigate curiosity about the cultural history of their parents’ home country.

5. One Half From the East – Nadia Hashimi (2016)

Nadia Hashimi’s first realistic fiction for young adults is about the bacha posh tradition of Afghanistan. In an unapologetically patriarchal society, the women in the family are usually destined for eternal incarceration within the house. Growing up in the big city of Kabul, 10-year-old Obayda was free to go to school, dance to Bollywood music and wear her favourite dresses. Forced to shift to the village after a bombing, with a now bitter father and a mother struggling to make ends meet with 4 daughters, they feel suffocated and judged for having no sons. Obayda’s mother then gives in to a relative’s advice of turning the young child into a bacha posh: a young girl dressed up as a boy, and accepted as such by society. The bacha posh have greater privileges than their sisters, for they can go to school, go to the market, play, run and so on. Obayda being forced to wear male attire and shear her hair were the only physical changes made to her. The rest of the transformations were sociological: renaming her as Obayd, and reorienting her entire behaviour to mirror that of a traditional man’s. The story follows her transformation to the day her mother decides to ‘change’ her back into a girl, and ends only after she comes to terms, in a way, with the second forced change.

The book is an amalgamation of themes such as gender identity-performativity-fluidity, personal choice, and women’s rights, underscoring everything with the heavy question of whether children are merely slaves to parental will. It’s meant to make young people aware about this still under-researched tradition, and help them realise that vulnerability due to age or gender and subsequent oppression are often universal, regardless of the geographic location.

6. Swimming in the Monsoon Sea – Shyam Selvadurai (2005)

Shyam Selvadurai’s coming-of-age novel about a 14 year old in Sri Lanka of the 1980s is special, as diaspora literature for children based on or around Sri Lanka is rare. Amrith is quite a regular teenager, worrying over the gaping hole of boredom that is the summer holidays. He is an orphan, being raised by the protective Auntie Bundle and Uncle Lucky, who also have two daughters of their own. Even though he is not quite over the deaths of his parents, he still manages to be excited about everyday schoolboy things like learning how to type, and practising for his school play. The arrival of his older, exciting cousin Niresh from Canada stirs up emotions in Amrith, setting off events which force both of them to confront their family’s past, the nature of their disturbing fathers, and in Amrith’s case, his sexuality.

The drama plays on themes like injustice, jealousy (much in the theme of Othello, the school play Amrith was practicing for), and discovering one’s ‘deviant’ sexuality in a time when there is no acceptance of it whatsoever. Young children struggling to come to terms with their sexuality, and those afraid to come out to a repressive family, might find this an encouraging read. It helps to gently plant the idea that belonging has to come from within, rather than from one’s geographical location, economic position, or even cultural identity.

Literature is an important lens through which to examine cultural shifts, as it is, in many ways, a microcosm for our society. Positive portrayals of same-gender love are slowly becoming more mainstream. Kai Cheng Thom’s Lambda finalist Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars is one such book and the latest addition to Young Zubaan’s list of kickass feminist books for children and young adults. (find the link to our web store at the end of the article). For this year’s Pride celebrations, we have curated a list of five books which pertain to the truth of living as a queer person in the global South, or as a queer person of colour in the North.

Literature is an important lens through which to examine cultural shifts, as it is, in many ways, a microcosm for our society. Positive portrayals of same-gender love are slowly becoming more mainstream. Kai Cheng Thom’s Lambda finalist Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars is one such book and the latest addition to Young Zubaan’s list of kickass feminist books for children and young adults. (find the link to our web store at the end of the article). For this year’s Pride celebrations, we have curated a list of five books which pertain to the truth of living as a queer person in the global South, or as a queer person of colour in the North. Translated from Marathi by acclaimed novelist Jerry Pinto, Sachin Kundalkar’s novel traces the story of a mysterious tenant who captures the hearts of two siblings Tanay and Anuja, when he arrives as an artist looking for lodging in their family home in Pune. The novel pairs interior monologues from Tanay and Anuja, both addressed to their beloved boarder, who charmed each of them before leaving without any explanation.

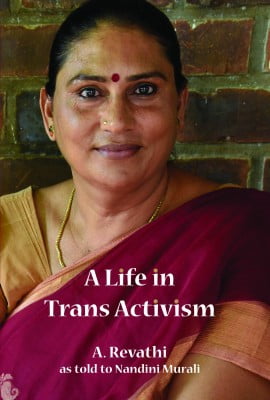

Translated from Marathi by acclaimed novelist Jerry Pinto, Sachin Kundalkar’s novel traces the story of a mysterious tenant who captures the hearts of two siblings Tanay and Anuja, when he arrives as an artist looking for lodging in their family home in Pune. The novel pairs interior monologues from Tanay and Anuja, both addressed to their beloved boarder, who charmed each of them before leaving without any explanation. Published in 2016 by Zubaan, A Revathi’s second book traces her life, and her work in the NGO Sangama, which works with people across a spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations. It narrates the tale of how she rose from office assistant to the director in the organisation. The first half of the book describes her journey as a trans woman, as she becomes an independent activist, theatre person, actor, writer and organiser for the rights of transgender persons. Later, Revathi offers insight into one of the least talked-about experiences in the gender spectrum: that of being a trans man. A Life in Trans Activism emphasizes the ways in which the trans identity intersects with other identities, and how these intersections contribute to unique experiences of oppression and privilege.

Published in 2016 by Zubaan, A Revathi’s second book traces her life, and her work in the NGO Sangama, which works with people across a spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations. It narrates the tale of how she rose from office assistant to the director in the organisation. The first half of the book describes her journey as a trans woman, as she becomes an independent activist, theatre person, actor, writer and organiser for the rights of transgender persons. Later, Revathi offers insight into one of the least talked-about experiences in the gender spectrum: that of being a trans man. A Life in Trans Activism emphasizes the ways in which the trans identity intersects with other identities, and how these intersections contribute to unique experiences of oppression and privilege. Babyji is a daring coming of age story of 16-year-old Anamika Sharma, a student in New Delhi. Abha Dawesar’s second novel details the exploits of Anamika as she romances three women, juggling her studies and her lovers while attempting to finish school. The story is set against the backdrop of Mandal Commission’s recommendations in 1980, which proposed the doubling of seats for backward castes. An upper-caste woman herself, Anamika uses her academic expertise and sexual prowess, to liberate herself from the Brahmanical mores of the society that she inhabits. Babyji is a brave exploration and moral enquiry into what it means to be a growing woman who is coming to terms with her own sexuality. This novel is the winner of the 2005 Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction and of the 2006 Stonewall Book Award for Fiction.

Babyji is a daring coming of age story of 16-year-old Anamika Sharma, a student in New Delhi. Abha Dawesar’s second novel details the exploits of Anamika as she romances three women, juggling her studies and her lovers while attempting to finish school. The story is set against the backdrop of Mandal Commission’s recommendations in 1980, which proposed the doubling of seats for backward castes. An upper-caste woman herself, Anamika uses her academic expertise and sexual prowess, to liberate herself from the Brahmanical mores of the society that she inhabits. Babyji is a brave exploration and moral enquiry into what it means to be a growing woman who is coming to terms with her own sexuality. This novel is the winner of the 2005 Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction and of the 2006 Stonewall Book Award for Fiction. Indra Das’s debut novel is a love story between two shape shifting werewolves, Fenrir and Gevaudan — a gay couple — and their companion, a young Muslim woman called Cyrah. The shape shifters exist on the margins of society: they wander into Shah Jahan’s empire, fleeing persecution in their homeland. Alok Mukherjee, a Bengali professor of history who narrates the novel, is still reeling from an engagement that was broken off after his affairs with other men came out in the open. The Devourers refuses to be pigeonholed into a single genre; it borrows tropes and writing devices from dark fantasy, speculative fiction and science fiction. A chilling saga that spans across various centuries and continents, this novel showcases Das’s incredible prowess with language and rhythm. The Devourers won the 29th Annual Lambda Award in LGBT Science Fiction/ Fantasy/ Horror category.

Indra Das’s debut novel is a love story between two shape shifting werewolves, Fenrir and Gevaudan — a gay couple — and their companion, a young Muslim woman called Cyrah. The shape shifters exist on the margins of society: they wander into Shah Jahan’s empire, fleeing persecution in their homeland. Alok Mukherjee, a Bengali professor of history who narrates the novel, is still reeling from an engagement that was broken off after his affairs with other men came out in the open. The Devourers refuses to be pigeonholed into a single genre; it borrows tropes and writing devices from dark fantasy, speculative fiction and science fiction. A chilling saga that spans across various centuries and continents, this novel showcases Das’s incredible prowess with language and rhythm. The Devourers won the 29th Annual Lambda Award in LGBT Science Fiction/ Fantasy/ Horror category. A collection of speeches and essays by a self-described “black lesbian feminist warrior poet,” Sister Outsider is considered a ground breaking work by Audre Lorde. This book contains a great mix of ideas and tones; it has poems, interviews, journal entries, and speeches interspersed with aphorisms. It proved to be an important and necessary tool in the cannon of progressive theory when it was first published in 1984. Lorde’s work centres the experience of black lesbians and critiques a mostly white, academic community of second-wave feminists for overlooking blacks, gays and women, as well as the elderly and the disabled in their theories.

A collection of speeches and essays by a self-described “black lesbian feminist warrior poet,” Sister Outsider is considered a ground breaking work by Audre Lorde. This book contains a great mix of ideas and tones; it has poems, interviews, journal entries, and speeches interspersed with aphorisms. It proved to be an important and necessary tool in the cannon of progressive theory when it was first published in 1984. Lorde’s work centres the experience of black lesbians and critiques a mostly white, academic community of second-wave feminists for overlooking blacks, gays and women, as well as the elderly and the disabled in their theories.