No products in the cart.

Return To ShopAugust is Women in Translation month. The campaign was started in 2014 by the translator and blogger Meytal Radzinski after she discovered the low numbers of women published in translation. Translated books only form three percent of published literature in English markets and only 30% of these works are written by women. As the month comes to an end, we have put together a compilation of some of the most compelling books we have translated. A collection of memoir, fiction, non-fiction and poetry, it offers fascinating stories from god-forsaken villages and chaos filled cities of India. Each of these books, originally published in a regional language, deserves a wider audience especially because these are stories marginalized by the mainstream. The authors— including a political prisoner in Kashmir, the wife of a communist leader in Andhra Pradesh, a domestic worker in Gurgaon, an eighth century Tamil poet and a contemporary one— are all women. Some of them spin beautiful fiction out of lived realities while for some just the honest story of their life leaves us astounded by the limits of our ignorance but all of them provide a new understanding of what it means to be not only a woman but a citizen of India.

A Life Less Ordinary by Baby Halder, translated from Hindi by Urvashi Butalia

Baby Halder had worked as a domestic help for a series of exploitative employers in Gurgaon before she landed, purely by chance, at the home of the retired academic Prabodh Kumar. With his encouragement she read the Bengali books at his home and eventually started writing her life-story. The story of a vanished mother, a murdered sister, marriage at the age of 12 and an abusive husband. In the words of The New York Times she “recounts her story in plain language without a trace of self-pity”. Sangeeta Pisharoty writes in her review for The Hindu that during a conversation with the author she found it difficult to absorb her methodical narration of her life’s struggles. Halder’s nonchalant narration is evidence of the extent to which violence is intrinsic to the life she had growing up as a dalit woman in Durgapur, West Bengal. Nothing can highlight the importance of what the book stands for more than these direct words of Halder “Many girls back home go through a similar life and yet nobody sees it as any different”. The book became a bestseller which highlights how removed society is from the everyday realities of those who work for us. That Halder was surprised by the response the book received should not come as a surprise to us.

Prisoner No. 100: An Account of my Days and Nights in an Indian Prison by Anjum Habib, translated from Urdu by Sahba Husain

The book is a passionate and moving account of the five years Anjum Habib, a young woman political activist from Kashmir, spent in jail after she was arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA). In an interview Anjum Habib said “Being a woman and that too from Kashmir makes your life in jail a living hell.” She describes how police officials in Delhi verbally assaulted her saying “You are a separatist leader of the Muslim Khawateen Markaz; we will strip you naked, take snaps and distribute them all over India, defaming you forever.” When she entered the jail premises, she was the only Kashmiri woman; the hostility of the other jail inmates, she said, will remain etched forever in her memory. A review of the book in Kashmir Lit says “To know that it is not fiction, but an exposition of the condition of living, breathing people, makes it profoundly disturbing.” Bashrat Peer, author of Curfewed Nights, has remarked “Everyone interested in Kashmir should read it” and has called it “A brilliant critique of patriarchy in politics, a searing tale of the terrible humiliations visited upon political prisoners, a poignant story of a woman who dedicated her life to political change in Kashmir, a passionate love letter to Kashmir.”

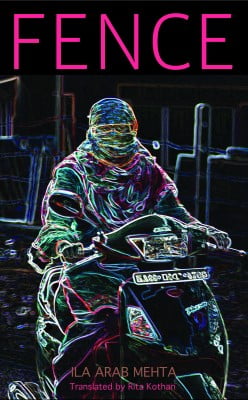

Fence by Ila Arab Mehta, translated from Gujarati by Rita Kothari

The cover of this book by the award winning Gujarati author sketches a girl on a scooty dressed in a burkha. The Indian Express review of the book remarked “The symbolic cover deserves appreciation. Seen through the burkha is only a pair of eyes— apprehensive, circumspect and moving ahead with confidence.” It symbolizes what the protagonist of the novel aims to achieve: mobility on her own terms. Fateema is a young ambitious woman who climbs over the fences of poverty and illiteracy to pursue an education and a job in the big city. Mehta was inspired to write the story when she read a piece by a Muslim woman in a Gujarati magazine on how difficult it was for her to find a house. Her protagonist dreams of buying her own house but in the deeply communalized society of Saurashtra a house can only be on either side of the fence—the Hindu or the Muslim. Fence explores the deep seated communal prejudices that work against Fateema’s arguably ordinary dreams. In the review for Indian Express, S.D Desai finds the book “Heartening, for Gujarati literature is largely unconcerned about the trauma the Muslim community suffers. Gujarati Hindu teachers supporting Fateema in her struggle bring a breath of fresh air, indeed. “

The Hour Past Midnight by Salma, translated from Tamil by Lakshmi Holmstrom

The Hour Past Midnight by Salma, translated from Tamil by Lakshmi Holmstrom

For many years no one knew that a woman (named Rokkaiah by her in-laws) confined within the four walls of her husband’s home in the rural interiors of Tamil Nadu was the sensational author known as Salma. She wrote secretly in the toilet at night and sent manuscripts to editors through relatives. She started writing because of the anger she felt when she had to stop going outside her home once she attained puberty. Her works include poems, short stories and novels all of them depict the life of women within the conservative Tamil Muslim community. Her poems, which are known for explicit sexual imagery, have received wide critical acclaim. The novel The Hour Past Midnight is based on her childhood in a village near Tiruchi. However, it is not an autobiography but as this review puts it “It is the story of the girl child in the deep South, the story of daughters and sisters and hapless mothers and grandmothers, all caught in an inexorable web of growing up, getting married, bearing children and dying. It is the story of “woman in the set framework”, her life’s purpose limited to four walls, the walls slowly rising brick by brick, inexplicably; this is not a story about breaking barriers.”

Motherwit by Urmila Pawar, translated from Marathi by Veena Deo

Pawar identifies herself as a Dalit woman writer, a Buddhist and a feminist and all three identities reveal themselves powerfully in this collection of short stories. The Hindu called them “unashamed and bold stories of the travails of the Indian woman.” Her heroines are clever women from all classes of society in urban and rural Maharashtra. They brave caste oppression, defy insults and are unhesitant in opposing their in-laws while guarding their interests. “These are the women sitting next to you on the Churchgate-Virar fast local, or processing your forms in the Pune municipal offices, or checking into the maternity ward in Pimpri-Chinchwad” says the review at LiveMint remarking that “the women sparkle with agency and complexity that is a delight to read.” Pawar’s writing is sprinkled with the characteristically coarse Marathi humour (which lends the book the titular wit). Asian Age writes about the translation “Deo meets the challenge by keeping to an earthy, conversational style”. The review at LiveMint recommends “slip her in alongside Mahashweta Devi and Ismat Chugtai and Jhumpa Lahiri and Anjum Hasan and every other writer with the skill to render the minutely personal as piercingly political.”

The Sharp Knife of Memory by Kondapalli Koteswaramma, translated from Telugu by Sowmya V.B.

Kotasweramma has always been popularly identified as the wife of Kondapalli Sitaramaiah, founder of the Maoist movement in Andhra Pradesh, even though she herself was a core member of the communist movement. Inspired by the Bolsheviks, Koteswaramma took up party life early on in life. She went underground in the forties, living a secret life, running from safe house to safe house. In her own words this struggle paid dividends when her famous husband deserted her after an extramarital affair. She educated herself, got a job, raised her grandchildren, wrote poetry and prose and established herself as a thinking person in her own right. The story of her life spans a century of the independence movement and the communist insurrection in Andhra Pradesh. The stories of her struggle against the odds accompany her deep understanding of the workings of the party and the fragility of the political institution. On its first publication in India, this moving memoir took the Telugu literary world by storm.

Seventeen by Anita Agnihotri, translated from Bengali by Arunava Sinha

Anita Agnihotri travelled extensively in Orissa and Jharkhand for her work as an IAS officer. Her travels inspired her to document the lives of those who remain in the shadow of India Shining. The characters of her stories and the images they evoke seem real because she works with details to eke out their lives of poverty and injustice. She does not believe in writing from the desk; she meets people and connects with them. She spins her stories around these experiences and as a reviewer puts it, her stories are perfect illustration of how fiction can begin in fact and not be limited by it. Apart from far-flung towns and villages, her stories are also set in metros and international suburbia, documenting the lives of landless peasants, migrant workers, abandoned wives and their companions in struggle. Seventeen is a collection of some of her stories from among more than a 100 of her published works. Apart from far-flung towns and villages her stories are also set in metros and international suburbia. Translated by Arunava Sinha, the book won the 2011 Economist Crossword Book Award for Translation.

Swarnalata by Tilottama Misra, Translated from Assamese by Udayon Misra

Considered one of the finest historical novels in Assamese Swarnalata is set in 19th century Assam when the forces of tradition were being challenged by the concepts of modernity. It takes the reader into the social milieu of the times when issues like widow remarriage and women’s education held centre stage. It traces the story of three Assamese girls, each facing personal struggles which reflect the larger societal truth of the times. Swarna, the daughter of privileged, educated parents cannot escape the biases faced by other women, her friends Lakhi and Tora are respectively a child widow and a convert to Christianity with a mind of her own. These girls are surrounded by revolutionary young men eager to break bondages of tradition. Swarnalata also provides a delectable blend of history and fiction by placing real historical figures like Rabindranath Tagore side by side with fictional characters. Arunava Sinha in his review has said “In capturing the collective aspiration of a people from a part of India whose literature is unjustly under-circulated, Swarnalata becomes a rich panel in the patchwork quilt that is contemporary Indian fiction.”

Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess, translated from Tamil by Priya Sarukai Chabria, Ravi Shankar

Andal, the eighth century Tamil poet, is the only female saint among the twelve Alvar saints of South India dedicated to the worship of Vishnu. Chabria and Shankar’s elegant translation of the corpus of poetry by Andal cements her status as the Southern corollary to Mirabai. However, as this review says “Her love for Vishnu is about an unequivocal affirmation of women’s sexual agency. Unlike Mira’s Krishna, Andal’s Hari is a full-bodied masculine presence. Like Andal’s wearing of the deity’s garland doesn’t defile it, her carnal longing for his form, while rejecting mere mortal lovers, also does not sully the bhakt-bhagwaan relationship.” This book translates Andal’s Tamil poems into contemporary English idiom, reimagining them as lyric poems keeping the philosophic meanings in the background. About the translation, Sumana Roy in her review for The Scroll said ‘The brilliance of the translators is also easy to see in the way they remain invisible, in the way we meet Andal directly, without the service of middlemen” hailing the Introduction for the book as “a great handbook for future translators on the subject”.

Here are some recommended reads from other parts of the world:

13 Translated Books By Women You Should Read

A Celebratory List of non-fiction books by leading thinkers and writers

An Essay on the Gender Politics of Translation

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.